This route dives into the history of the United Fruit Company and the Standard Fruit and Steamship Company during the early to mid 20th-century in New Orleans. These companies had a lasting disastrous impact on the economic, political and social landscapes in Latin American countries. Journalists took to calling United Fruit “el pulpo” (“the octopus”) because its tentacles were everywhere. The exploitation enacted on Latin American countries and people is yet another form of oppression that needs to be called out and fought against.

Turn by turn directions can be found here: https://goo.gl/maps/qUkP6FZtZnQABLy38

Stop A: Chartres & Desire

By 1968, Standard Fruit had been acquired by the Castle & Cooke Corporation, which also purchased the Dole Hawaiian Pineapple Company. In the 1990s, the entire conglomeration was renamed as the Dole Food Company.

Stop B: United Fruit Company’s old headquarters

The banana trade had devastating and violent social and political effects in many Latin American countries. For an in depth look at the “Banana Republics” and Banana Wars, watch this documentary, Banana Land: Blood, Bullets & Poison. As a Colombian resident says in this film, “If we take a look at our social and political surroundings, we see that they are scarred by the money of multinational banana companies and their mad desire to seize land, maintain economic power, and to keep the community and society in a state of economic and social slavery.”

Stop C: Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine

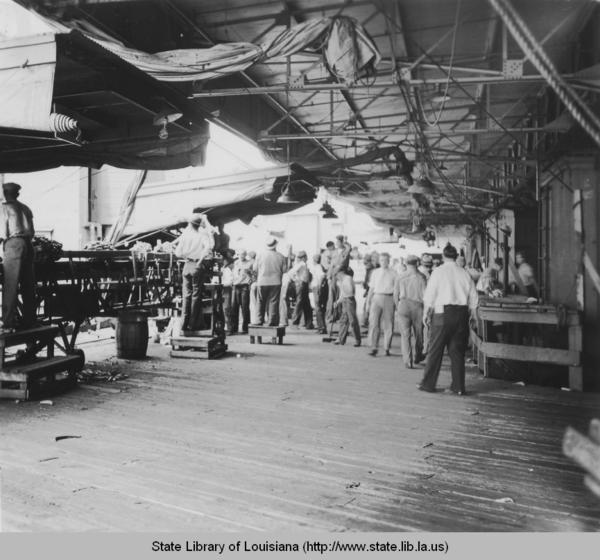

Stop D: Thalia Street Wharf

During the course of construction of the railroad, Keith had begun experimenting with bananas as a cheap, bountiful, and local source of food for laborers. In 1870, Bananas were a relatively rare delicacy in the United States, but from the mid-1870s on Keith began importing the fruit from Limón to the port of New Orleans. Unlike the railroad itself, banana importation was wildly successful, and Keith quickly became a dominant force in the burgeoning Central American banana trade.

Meanwhile in Boston, Andrew Preston became interested in founding a larger banana import company, and eventually was part of a group of ten men who in 1887 founded the Boston Fruit Company. Preston and the Boston Company invested heavily in Jamaican agricultural land and so controlled the source of their bananas, but Preston also developed refrigerated distribution networks in the United States to sell bananas outside of major seaports. In 1899, Preston’s Boston Fruit Company merged with Keith’s Tropical Trading and Transport Company to form the behemoth United Fruit Company. United Fruit soon began to gobble up other companies, not all of them banana-related. For instance, in 1901 the Guatemalan government hired United Fruit to manage the country’s postal service.

From Emily Perkins and the Historic New Orleans Collection, read the essay “Bananas, quarantines, and the octopus: United Fruit Company’s PR stunt in Central America”: https://www.hnoc.org/publications/first-draft/bananas-quarantines-and-octopus-united-fruit-companys-pr-stunt-central

This wharf was also known to be the epicenter of the 1905 yellow fever outbreak in New Orleans, which began when Italian laborers unloading a shipment of bananas contracted the illness (which is spread by mosquitoes). The disease quickly spread through the city, and federal authorities eventually fumigated the city. By the time the city brought the epidemic under control in October of 1905, a total of 452 people had died.

Finally, the Port of New Orleans is also connected to an initial, failed attempt to overthrow the democratically elected government Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz. In 1952, the Central Intelligence Agency began holding meetings with representatives of Carlos Castillo Armas, a former officer in Guatemalan Army living in partly self-imposed exile in Nicaragua after earlier coup attempts against Árbenz. Those meetings developed in Operation PBFortune, which was financed by the United States (via the CIA), the United Fruit Company (which was concerned about threats to its status as Guatemala’s largest land owner), and the right-wing dictators of Nicaragua, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic.

Using a cargo boat lent to them by the United Fruit Company and weapons (including 250 rifles, 380 pistols, 64 machine guns, and 4500 grenades) seized by customs inspectors at ports in New York City, the CIA retrofitted the boat and prepared to ship the weapons to Armas’ forces in Nicaragua. To disguise the contents of the ship, the CIA paperwork falsely identified the weapons as “farm equipment,” and Armas and the CIA began planning for an April 1953 coup.

Ultimately, though, both the Nicaraguan and Honduran Ambassadors raised questions about the boat’s actual contents, and the operation was scuttled by President Eisenhower. The CIA, however, continued to fund Armas, and in June 1954 Armas led military forces into Guatemala from El Salvador and Honduras and overthrew Árbenz.

(For more on Operation PBFortune and shameless CIA intervention in Guatemala, see – among many, many other works – https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3072&context=etd or https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000135796.pdf). Alternately, The Harvard Business Review has a conversation with Professor Geoffrey Jones, discussing the 1954 coup and the role of United Fruit: https://hbr.org/podcast/2019/07/the-controversial-history-of-united-fruit, or check out this “story map” from Adam Kellar and Jaren Foster about the so-called “Banana Wars” in Honduras, Guatemala, and other nations impacted by colonial capitalism: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/1c0c992fe46b47e8a411e96f5f69f2de

Stop E: Sam “BananaMan” Zemurray’s old home

The United Fruit Company lives on today, although now in the guise of “Chiquita Brands International Incorporated.” UFC began using the brand name “Chiquita” in the 1940s and 1950s, but did not formally adopt the name for the entire corporation until 1989.

Samuel Zemurray’s daughter Doris, who grew up in this house, and her husband Roger Thayer Stone founded Tulane’s Latin American Studies Center.

While you are riding, bring masks and hand sanitizer, respect physical distancing, and make sure that you have an emergency contact who knows where you are and can pick you up if needed. We also have some more in-depth tips for safe biking in the pandemic, check them out! Please be aware that NOLA to Angola cannot provide logistical or emergency support to individual riders this year. Take care, and safe riding!