Turn by turn directions can be found here: https://goo.gl/maps/UfwkhbZLkgU4M2MVA

Algiers has beautiful brand-new bike lanes that’ll be ready for riding in October. Check out this map to see their progress.

Stop A: The Algiers Ferry & Courthouse: Purchased Lives, Early Jewish History in Louisiana, Monuments to Injustice

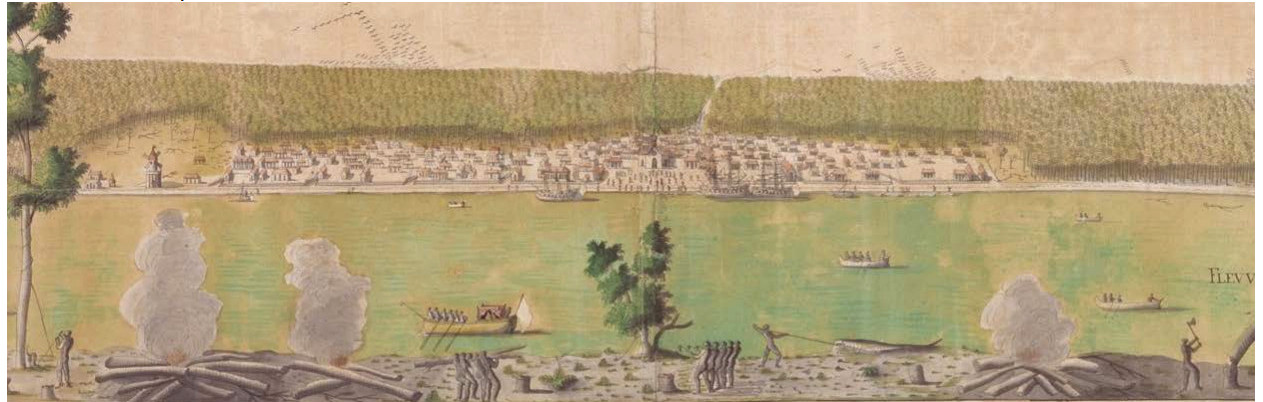

By the early 1730s, the Company Plantation spanned over 3500 feet of riverfront. Its population, according to a 1731 census, was 224, of whom 99 percent were enslaved. At times the Black population would swell to over 400, as enslaved visitors from New Orleans arrived on pirogues to assemble with brethren on Sundays, an antecedent of the Congo Square gatherings of the 1800s.

In 1731 the Company of the Indies went bankrupt. Control of the Louisiana colony shifted to the French government, and the importation of enslaved people slowed. The plantation on this site fell into disuse. Governor Bienville (who now had command of the Company’s lands) granted portions of the Company’s real estate to his colonial accomplices.

In the 1768, Isaac Monsanto purchased a plantation in this area that had been built by Bernard de Verges, an engineer for the French colony. Monsanto was banished from the colony the following year, when control was ceded to the Spanish. Monsanto’s plantation house (the modestly named ‘Trianon’) was located on the spot where the Algiers Courthouse is today.

Additionally, the historical marker at this site is also one of only a handful of public memorials that addresses the slave trade in New Orleans.

Stop B: Parish Line

Just this past June, the New Orleans Police Department used tear gas and rubber bullets on peaceful protesters attempting to cross the bridge. Both incidents (in 2005 and 2020) were rationalized as necessary for public safety. Whose safety do these actions protect? Who are the police serving?

Stop C: Gretna/Mayor’s Court

These arrests are overwhelmingly for non-violent offenses. In 2013 10% of Gretna’s arrests were drug-related. 14% of arrests were for drunkenness or disorderly conduct. 65% were for “other offenses”- violations that are so obscure and petty that they’re not included in crime statistics. Think: tickets for not using a turn signal, citations for walking in the road, tickets for going one mile over the speed limit, tickets for having the corner of the registration sticker on your license plate covered. While the offenses themselves are inconsequential, the effect of being arrested by Gretna for one of these trivial, imaginary crimes can be profoundly damaging.

The punishment for the majority of these offenses is a fine. If you’re not able to pay the fine off quickly, there are also fines for nonpayment of fines. Too many unpaid fines and you’ll get a court date, which triggers even more fines. Made your court date? Then you get fees, and will possibly be threatened with arrest if you can’t make an immediate payment towards your outstanding debt. Missed your court date? That means more fines and possibly warrants. And then the next time Gretna police stops you because you jaywalked or your windshield is cracked you’ll wind up arrested and in jail.

Like many towns, the money derived from fines, fees, and forfeitures goes into a municipal fund. Nationally, these types of fines make up 1% of the average city budget. In Gretna, 15% of the budget comes from harassing people of color and exploiting financial vulnerability.

The second floor of Gretna’s City Hall (just across from the old ferry landing where this bike path ended) is headquarters for this racket. Every day dozens of people file up to the court offices in that location to pay what the city has demanded of them. There is extensive further reading at the bottom of this page about an illegal arrest quota scheme revealed by police whistleblowers, the highly suspect involvement of the mayor’s office in the collection of fines and the multiple federal lawsuits which as of yet have not put an end to cash register justice in Gretna. Let’s get out of here now, OK?

Stop D: Algiers Playground: We Shall Overcome

In March of 1955, the NOPD arrested fourteen children for using this playground, which at the time was designated for white use only. After Black schoolchildren entered the grounds police officers took them to jail, where they were detained for hours before seeing their parents. Parents of the arrested children were then forced to sign statements charging their children with being delinquents.

Witnesses to the arrests described the police tactics as “Gestapo-like,” and “Nazism.” As one small boy crawled under the fence to avoid arrest, “a policeman placed his foot on the child’s head.” All of the children had racist and profane obscenities shouted at them.

Days later, it happened again when nine more children were arrested for using the playground. What made the actions of the NOPD exceptionally reprehensible was that the whites-only playground had gone unused for years.

Stop E: All Saints Catholic Church

Stop F: The NOPD’s 1980 reign of terror

The night after the murder 20 officers went into the Fischer homes and kicked down doors at gunpoint, grabbing any young men that they found. They had no warrants for anyone’s arrest, and did not explain what or who they were looking for. NOPD then marched the young men through the development with their hands up, holding their guns on them like prisoners of war. The NOPD returned to the Fischer Development throughout the week following Neupert’s death to continue terrorizing residents.

The NOPD ultimately took six young men from the Fischer raids into police custody. They told of being handcuffed or tied to chairs, then beaten by police with a hardback city directory and “bagged”. By suffocating people with plastic bags, police left no telltale marks on witnesses whose “voluntary statements” were extracted for a breath of life. Two men were taken into the swamp and marched onto a wooden dock off a levee, then had a gun fired next to their heads in a mock execution to try to get information about Neupert’s murder.

The weeks of police violence led to the murders of four innocent people.

First to be murdered by the NOPD was Raymond Ferdinand, a 38-year-old Fischer resident who was stopped by officers during one of their assaults on the development. He was shot in the back of the head and neck after officers claimed he had pulled a knife on them.

Days later, James Billy, Reginald Miles, and Miles’ girlfriend Sherry Singleton were all killed simultaneously in police raids on 2 separate residences. These raids were based on accusations made under duress from the 2 men who were mock-executed in the swamp.

At 2:45 AM, sixteen police officers converged on this neighborhood with no intent of serving warrants, making arrests, or bringing any of the suspects into police custody. They were looking for revenge. All of the Black officers assigned to the Neupert investigation were excluded from the raid.

Eight officers went to 1133 Teche Street, and murdered Miles and Singleton. Miles was shot to death as he got out of bed. Sherry Singleton was killed while she was laying in the bathtub, naked. Her 4-year old son was with her, hiding behind the bathroom door. Police said Miles drew a gun on them and that Singleton’s gun jammed as she tried to fire.

Eight officers went to Billy’s residence here at 1137 LeBoeuf Street and pulled his girlfriend and infant son out of the house. Billy’s girlfriend stated “when the police brought me out of our house, I saw the dead wagon (the vehicle used to transport bodies by NOPD) was parked in front of the door, then I heard the shots.” Billy did not make an attempt to escape nor did he have a weapon when police started firing. The police said Billy “came up smoking”.

Every officer that participated in the murders of Miles, Singleton and Billy stuck to the story that all 3 had shot at police. NOPD administration and the mayor stood by the officers involved.

The people of New Orleans organized to demand repercussions. They held protests, leafleted, and formed the African American Police Brutality Committee. Black leaders threatened an economic boycott of downtown New Orleans during the winter holidays if no action was taken. Michael Williams of Community Action Now even padlocked the doors of the Patrolman’s Association of New Orleans while 200 officers were inside having a meeting. In June of 1981 (six months after the murders), with no punishments yet handed down from the city or the courts, protesters occupied the Mayor’s office for 3 days.

While a federal investigation into the killings had turned up hundreds of accounts of warrantless raids, beatings by the NOPD and confessions coerced by violence, there was no movement in the case until a source within the NOPD came forward. The lone Black NOPD officer who was present at one of the fatal raids told the FBI that “these people were murdered, that they didn’t have guns.” Nonetheless, a state grand jury declined to indict anyone. A federal grand jury handed up a lengthy indictment for conspiracy to violate the civil rights of the people that NOPD questioned in the Neupert investigation. This indictment did not include charges for what is perhaps the ultimate civil rights violation, murder by the police.

Despite having a cooperating witness from the NOPD, no one was ever charged for the deaths of Ferdinand, Singleton, Miles or Billy. Three homicide detectives were ultimately convicted on the federal civil rights charges and spent five years in prison each. Four other officers were acquitted. More than $2.8 million was be paid by the city in settlements with plaintiffs who were held against their will, beaten by police or traumatized by the murders of their loved ones.

The protests launched by community activists in the aftermath of

the Algiers murders resulted in the creation of an independent office for investigating police and government misconduct. At the time, many hoped the NOPD’s reign of terror in Algiers would have lasting consequences and be the impetus for significant reform.

It did not.

Stop G: Maroon Settlements: Purchased Lives

A small maroon hideout was documented in this area in 1781. At the time, this land was marshy forest behind the plantation of Jean Bienvenu. Two escapees were found in a temporary encampment- Juan Bautista, who had escaped a plantation in St. Amant and Pedro, who had fled all the way from a plantation in Pointe Coupée Parish. The former boundary of Bienvenu’s plantation and the cypriere behind it have been outlined on map embedded at the very top of this page- plantation in yellow, treeline in green.

Both Juan Bautista and Pedro were part of a larger community of about fifty other maroons. They moved between camps in the cypress swamp at the back of plantations and larger, more remotely located settlements. One of the most established maroon settlements was located behind a sawmill located in what is today the Barataria preserve; the members of this community were employed at the sawmill, grew vegetables and wove baskets which were brought to the city to sell. Another settlement was located in ‘Terre Gaillard’ (‘Land full of Life’ in French) on the edge of Lake Borgne, established by the legendary & fearless maroon leader St. Malo. (For more on St. Malo and Terre Gaillard, check out Cierra Chenier’s outstanding history over at Noir ‘N’ NOLA.)

Stop H: Folk Art Zone

Stop I: Henry Glover: 15 Years After Katrina

Henry Glover was a 31 year old resident of Algiers who had traveled to his mother’s house off Behrman Highway to ride out Katrina with his family. Four days after the storm, on the morning September 2nd, Glover and a friend had gone out to look for food and other supplies. They were walking in the area behind where the Dollar Tree is now located on General de Gaulle Drive when a shot was fired, hitting Glover in the chest. (Sites related to this tragedy have marked with black pinpoints on the map embedded at the top of the page.)

Glover’s friend and other witnesses at the scene could not pinpoint where the shot had come from, or understand why it had been fired.

Officer David Warren of the NOPD had been posted up across the parking lot from where Glover was shot. Warren was on the second floor of the strip mall, armed with his personal assault rifle. Warren reported over police radio that he had discharged his weapon, but did not indicate that the shot he fired had hit anyone.

Glover’s friend yelled out for help. Officer Warren did not respond. Glover’s brother was nearby and hurried over on foot; a passing driver in a white Chevy Malibu also stopped to help. The gravely injured Glover was moved to the backseat and Glover’s brother joined him in the vehicle. The driver of the Malibu thought Glover might not survive the trip to West Jefferson hospital, so he drove to a makeshift NOPD command center at the Habans school, located just across DeGaulle in 2005.

Upon arriving at the school, the driver and Glover’s brother were pulled out of the car by NOPD and handcuffed. Both were beaten and berated by Lieutenant Dwayne Scheuermann and Officer Greg McRae; the driver was hit in the face with the butt of an M-16. When the driver and Glover’s brother were released, they were told that the NOPD would be keeping the Chevy Malibu because it was now “part of a police investigation”. A police officer with signal flares in this back pocket then drove the Malibu off towards the river; Scheurmann followed in another vehicle. Glover was still slumped in the backseat.

A week later on September 9th, two volunteer first responders were on foot patrol at this spot on the levee. They spotted a burnt-out white Chevy Malibu in the batture. Glover’s badly burned remains were in the backseat with what appeared to be a gunshot wound at the side of his head. The officer who found Glover said ‘The magnitude of the way it was destroyed, it was telling a story- “I don’t want no one ever to find out what I did.”‘

The remains stayed in the car for another week before they were removed. Later in September of 2005 Glover’s mother filed a report about her son’s shooting, the beating that followed and his disappearance in the stolen car. She made that report at the NOPD’s Fourth District station, which you can see from this spot. This station was staffed by many of the same officers who had been at the temporary command post Glover disappeared from. Glover’s remains would not be identified until 2007.

It would take another two years for the story of Glover’s shooting, the assault by the NOPD and the burnt-out car on the batture to be picked up by the media, then investigated by the Department of Justice.

In 2010, federal civil rights charges were brought against NOPD officers Scheurmann (who had beaten Glover’s brother and the man who drove them to seek help), McRae (who participated in the beating, drove the vehicle with Glover inside to the batture then threw a lit signal flare into its backseat) and Warren (who had shot Glover). Scheurmann was acquitted. McRae was sentenced to 17 years in prison, which was later reduced to 12 years by an appeals court. Warren was initially sentenced to 25 years in prison for Glover’s murder, then acquitted at a new trial which resulted from an appeal.

Please take a moment to remember Henry Glover while you’re in this spot. After you’ve left, please continue to remember him through the actions you take to demand the end of policing as we know it.

Stop J: Chalmette Ferry Dock/Chalmette Refinery: Poisoned Ground

Stop K: Cut Off

“This neighborhood is very unique. It’s, you know, always everything in this community, always was owned and operated by blacks. You know, we had our own school. We broke the ground in governing the building of the school. We had our own church, we had our own grocery store. Everything down here. We didn’t know what it meant to rent something—everybody had their own property.”

“I say that because most places in the black community, whites had owned everything, the grocery store and everything, but not here. So, we was very independent people…we didn’t know what it was to, when you had to go through the side door. When blacks were not allowed to go in the front door, in my time if you wanted something at one of those places, you had to use the side door and we wasn’t used to that kind of stuff. Everything, we’ve got what we need right here. Very rich community, of which it is inherited: church, school, you name it.”

– Isiah Riley, Deacon of the Second Baptist Church of Cut Off, founded 1868

Oral history has it that this neighborhood came to be just after the Civil War, when a landowner named Puisson began selling property to African-Americans at what was then a low price ($25 or $30 for a lot). This angered white landowners, who attacked the Puisson family. The Reverend Reason Boyd intervened and de-escalated, and in gratitude the Puissons gave Boyd a large piece of property between today’s Sullen Place and Casimire Street.

Boyd’s property was settled by people recently freed from slavery and many of their descendants still live here. Benn’s Grocery was established in 1886 in the same location where it is today; it is still owned and operated by the founder’s great-great-grandson. (If you stop in here, WEAR A MASK!) The Second Baptist Church was founded in 1868, and has had 5 pastors in its 152 years. Shotgun homes can be seen along this part of the route- some have had additions and renovations made; others look to be as old as the neighborhood itself.

Stop L: ExhibitBE

‘ExhibitBE’ was created for the 2015 Prospect.3 biennial; it is seen as the most important New Orleans artwork of the 21st century. Odums nonetheless believes that “Overall, [ExhibitBE] was a failure…we weren’t able to hold the owners accountable and turn it into something. As a spectacle, it was something amazing, but I don’t like the fact that…it still is in the condition it was in.”

Murl Street is a public thoroughfare; parts of ExhibitBE are visible from the street. There is a large pile of broken concrete at the entrance gate to deter access. The buildings where ExhibitBE are located are private property; please be aware that entering the site without permission is trespassing.

Recommended further reading & viewing:

Baratunde Thurston, ‘Beyond the NatGeo Report on Policing in Gretna (Parts 1-3)’

Mark Gimein, ‘Welcome to the Arrest Capital of the United States’

Michael Isaac Stein, ‘Police Lawsuits Provide a View of Cash Register Justice’

Leonard Moore, Black Rage in New Orleans. LSU Press, 2010

Janny Densmore, ‘Algiers Killings’. BOMB Magazine, April 1982. Available online at https://bombmagazine.org/articles/algiers-killings/

Cierra Chenier, ‘Jean Saint Malo: The Man, The Maroon, The Martyr’

Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Africans in Colonial Louisiana. LSU Press, 1992

‘Law & Disorder.’ Frontline. PBS. First broadcast August 25, 2010. Available online at https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-law-disorder/

A.C. Thompson, ‘Body of Evidence’

Dari L. Green, PhD. Lower Coast of Algiers. Arcadia Publishing, 2018

Rick Weill, ‘Cut Off Community Portrait’

Richard Campanella, The Westbank of Greater New Orleans: A Historical Geography. LSU Press, 2020

While you are riding, bring masks and hand sanitizer, respect physical distancing, and make sure that you have an emergency contact who knows where you are and can pick you up if needed. We also have some more in-depth tips for safe biking in the pandemic, check them out! Please be aware that NOLA to Angola cannot provide logistical or emergency support to individual riders this year. Take care, and safe riding!